by Greg McCollum

My father, Warren Harvey McCollum, was born in 1921 near Spring Garden, Alabama in Cherokee County, the oldest of ten children. He left home when he was sixteen to find work, but “you couldn’t even buy a job." With only a 6th grade education and no training other than working on his sharecropper parent’s farm, in October 1940 he joined the United States Marine Corps.

Harvey McCollum (center) at Parris Island, South Carolina, 1940.

What follows are photographs from his personal collection, an edited transcript of an audio recording made shortly before his death in 1994, plus photographs and details of the Guadalcanal Campaign (in blue) from the U.S. Navy’s official history (found here).

**********

After basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina we were shipped to Samoa and from there, in April 1942, on to American Samoa to protect the Seabees construction crews. They were building an airport.

We were getting infantry training all the time we were there. That's the thing that paid off the most for us because we were going through the conditions nearly like the real thing. I was in an artillery task force and I had a brother, Bill, who was in an infantry task force.

GUADALCANAL

In the six months between August 1942 and February 1943, the United States and its Pacific Allies fought a brutally hard air-sea-land campaign against the Japanese for possession of the previously-obscure island of Guadalcanal. The Allies' first major offensive action of the Pacific War, the contest began as a risky enterprise since Japan still maintained a significant naval superiority in the Pacific Ocean.

U.S. Marines rest in the field on Guadalcanal, circa August-December 1942. Most of these Marines are armed with M1903 bolt-action rifles and carry M1905 bayonets and USMC 1941 type packs. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

Nevertheless, the U.S. First Marine Division landed on 7 August 1942 to seize a nearly-complete airfield at Guadalcanal's Lunga Point and an anchorage at nearby Tulagi, bounding a picturesque body of water that would soon be named "Iron Bottom Sound". Action ashore went well, and Japan's initial aerial response was costly and unproductive. However, only two days after the landings, the U.S. and Australian navies were handed a serious defeat in the Battle of Savo Island.

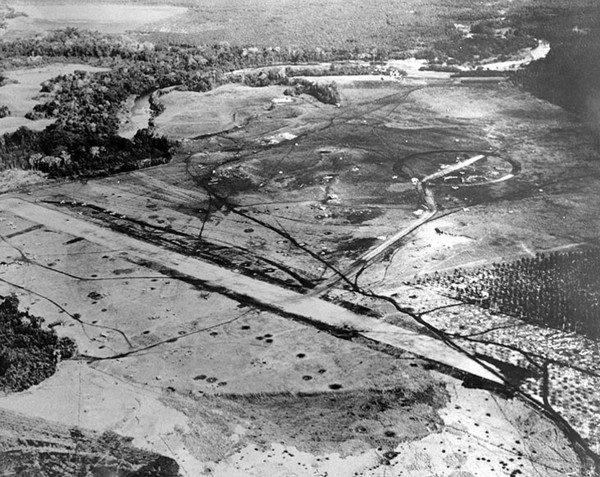

A lengthy struggle followed, with its focus the Lunga Point airfield, renamed Henderson Field. Though regularly bombed and shelled by the enemy, Henderson Field's planes were still able to fly, ensuring that Japanese efforts to build and maintain ground forces on Guadalcanal were prohibitively expensive. Ashore, there was hard fighting in a miserable climate, with U.S. Marines and Soldiers, aided by local people and a few colonial authorities, demonstrating the fatal weaknesses of Japanese ground combat doctrine when confronted by determined and well-trained opponents who possessed superior firepower.

Henderson Field photographed in August 1942, after U.S. aircraft had begun to use the airfield. The view looks about northwest, with the Lunga River running across the upper portion of the image. Iron Bottom Sound is just out of view at the top. Several planes are parked to the left, and numerous bomb and shell craters are visible. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

At sea, the campaign featured two major battles between aircraft carriers that were more costly to the Americans than to the Japanese, and many submarine and air-sea actions that gave the Allies an advantage. Inside and just outside Iron Bottom Sound, five significant surface battles and several skirmishes convincingly proved just how superior Japan's navy then was in night gunfire and torpedo combat. With all this, the campaign's outcome was very much in doubt for nearly four months and was not certain until the Japanese completed a stealthy evacuation of their surviving ground troops in the early hours of 8 February 1943.

After the invasion got started on Guadalcanal, (the Americans) were just about to take it, but we had to have reinforcements. The Japanese had control of the seas. We had those old Higgins boats. They decided to go in and land us. We went in one early-morning on a protected beach. We started unloading all of our gear and all of our equipment as fast as we could.

The first plane I ever saw shot down was one of our planes that first day. The cruisers would carry one or two seaplanes. Maybe (the pilot) should've known better. All of our ships were out in a big bay, some two to three thousand feet out. Everybody was trigger-happy anyway, expecting Japanese planes to come in anytime. The seaplane got down real low, about ship level, and starting circling around. One fool thought it was a Japanese plane and it only takes one shot to get the whole bunch going. They started firing at it with machine guns off the ship. Men on the beaches were shooting with rifles. They knocked that plane down and it sunk.

We worked until well before dark getting our supplies and everything we had to have off those ships. Then, those ships picked up anchor and away they went. They couldn’t stay there at night and take a chance on getting attacked by the Japanese fleet so they headed out and left us. We were left on the beach with what little equipment we had.

The Japanese had a plane - it was called a Zero - and it was a lot faster than anything we had. The Japanese would come in and then have a dogfight with our airplanes. Our bivouac area was right beside the airport. When they had one of those dogfights you had a front row seat. You could see every bit of it.

My artillery outfit supported one whole task force of the infantry, my brother’s task force. We stayed in our same position so we could shoot over them and we didn't have to move each time they moved. To give the other troops a rest, they would send our battalion or task force up on the line.

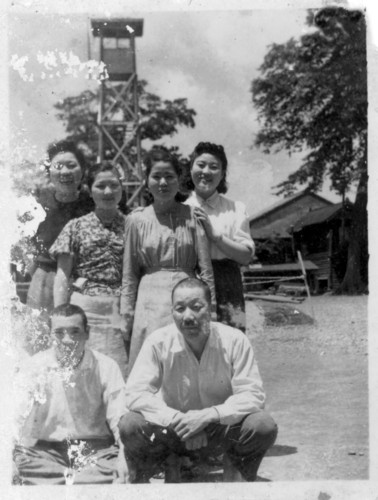

Harvey McCollum sits on the left.

Later, when the Japanese were having a hard time of it, they weren't able to take the island. They couldn't get an aircraft carrier close enough to do the job, to make an attack on us so they got within range that they could fly their Zeros into us, but they didn't have the fuel to get back to their carriers. They sent in about fifteen or twenty of those Zeros, but our old boys got pretty smart. One of those Zeros would get on him firing at him, but our pilots were just better pilots. They had more training and know-how. That lasted for about an hour until they had all those Zeros shot down.

Japanese Navy Type 1 land attack planes fly low through anti-aircraft gunfire during a torpedo attack on U.S. Navy ships maneuvering between Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the morning of 8 August 1942. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

The Japanese finally made a decision that they were going to send enough force to get us out of there. The way they jammed their people in those transports, they could carry as many troops on one transport ship we could carry on two. We knew they were coming and we were sending out our planes as far as we could, searching to see if we could spot their fleet.

Our planes finally spotted their fleet heading our way. We were right at the airport and they started knocking out all the planes on the ground. They shelled and shelled and shelled, and we didn't have anything close enough to stop them except coastal guns.

Wreckage of a SBD scout-bomber, still burning after it was destroyed by a Japanese air attack on Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, 1942. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

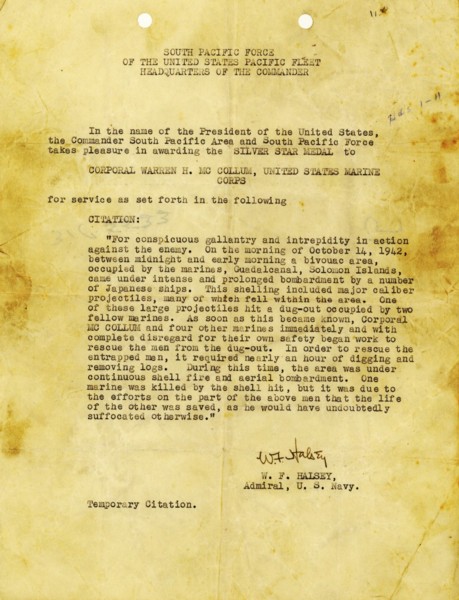

Everybody had their foxholes dug and covered over with coconut logs, and dirt over that, with a little doorway to get in. Right next to my hole was another foxhole that got hit with a direct shot. A couple of us got over there and started digging them out. We didn't have to dig them out, but we did. The Japanese were still firing. There was one that we got out alive.

I had a lot of friends who were killed, a good many. You just have to…. When a man's dead, he's dead. There wasn't anything could be done about it.

The Silver Star awarded to my father. The final citation was signed by the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, but having "Bull" Halsey's signature on the temporary one (shown above) isn't bad.

They did all the damage they wanted to and I got up out of the hole and looked around and it looked like the whole island was on fire. From the palm trees to the planes, everything was burning. It looked like every plane we had was gone.

Our communications weren’t too good. We just had little walkie-talkie radios. They had to have somebody to run a message down to the troops that were supporting the beach and another ol’ boy and myself volunteered to carry the message. It was dangerous to even get up out of your hole, to rise or stand up, because somebody was liable to shoot you including your own men because they were trigger-happy.

It was about half a mile from the airport to the beach through the coconut groves so we took off with the message which had to go to a certain outfit at a certain outpost. We delivered the message and stayed there the rest of the night.

Harvey McCollum on right. The reason someone is pointing a gun at him is unknown. Perhaps a card game gone wrong?

The Japanese didn't make a landing that night although we were scared they were going to make one. Before daylight the Japanese were gone and we were left to clean up and repair everything.

The next night the Japanese made another run and did some shelling. Our (naval) forces had placed themselves way out beyond the island and you could see ships blowing up. You could see shells being fired. They just had the whole sky out there lit up and every time you saw a great big fireball, you knew a ship had just been blown up.

U.S. Navy ships firing at attacking Japanese carrier aircraft during battle, 26 October 1942. USS Enterprise is at left, with at least two enemy planes visible overhead. In the right center is USS South Dakota, firing her starboard 5"/38 secondary battery, as marked by the bright flash amidships. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

Come the next morning some of us went down to the beach, to this big bay where we had landed. We had destroyers and cruisers that were crippled, maybe just enough power to pull themselves in, coming into that big lagoon down there, shot all to pieces.

USS Minneapolis at Tulagi with torpedo damage received in battle. Photograph was taken on 1 December 1942, as work began to cut away the wreckage of her bow. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

We had won the battle and destroyed their main force. They did have three transport ships that got through and came in the next day to the beach way up north of us. They were disabled and wanted to unload the troops they had left. All the planes we had left were just a-bombing and strafing those ships just as fast as they could go. They came in mighty slow and just rammed up on the beach. Our planes bombed and strafed those all day.

Harvey McCollum on Guadalcanal. Note the pistol on his right side.

Guadalcanal was expensive for both sides, though much more so for Japan's soldiers than for U.S. ground forces. The opponents suffered high losses in aircraft and ships, but those of the United States were soon replaced, while those of Japan were not. Strategically, this campaign built a strong foundation on the footing laid a few months earlier in the Battle of Midway, which had brought Japan's Pacific offensive to an abrupt halt. At Guadalcanal, the Japanese were harshly shoved into a long and costly retreat, one that continued virtually unchecked until their August 1945 capitulation.

AUSTRALIA and Back to the

States

I left Guadalcanal on December 4, 1943 going to Australia. We were all sick with malaria, give out, shell shocked, so we had to have some rest. By that time they had gotten in a few more battalions of the Army and maybe some more battalions of the Marines.

We stayed about nine months in Australia and got rested up and resupplied. Then, we had to go up to New Guinea. Part of New Guinea was still fighting. After a while they began to rotate some of the troops back home. We were on our way back to California. I was one of the first ones to get rotated and we passed by close enough to Guadalcanal to see those rusty Japanese transports still rammed up on the beach.

A Japanese cargo ship, the Kinugawa Maru, beached and sunk on the Guadalcanal shore, November 1943. She had been sunk by U.S. aircraft on 15 November 1942, while attempting to deliver men and supplies to Japanese forces holding the northern part of the island. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives.

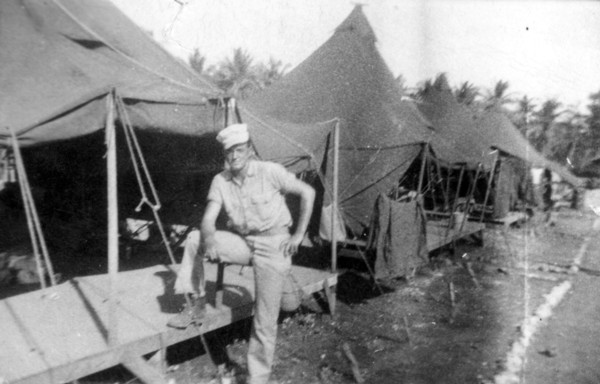

Harvey McCollum in San Diego, California.

We stayed in the states for about nine months in North Carolina. We had been going to Greensboro. There were about four of us going up there and we decided that we were going to go again. There wasn't anybody supposed to have any liberty. We decided we were going one more time. We caught a tractor-trailer that was bringing in supplies to the camp. He was leaving the next morning and we talked him into letting us ride with him as far as we could.

We spent the weekend at Greensboro, North Carolina and got the Greyhound bus back. We got in about 4 o'clock and they had a little old platoon leader named Metcalf. I walked in and he saw me and said, “Where in the world have you been?” I answered, “I've been to Greensboro, North Carolina. I took the weekend.” He was just all shook up, thought he was going to lose his command I guess.

They court-martialed us and took two or three months pay from me, but they didn't take any rank. I think I was a corporal at that time. I had already gotten one court-martial. We had gotten into a fight with a policeman, an iceman, and a deputy sheriff at a little restaurant up at Highlands, North Carolina.

At ease, between battles with Japanese and fistfights with cops.

Then, we had to go back overseas again. I’d just as soon go back overseas as to put up with all the baloney* going on at camp. They were training us with small arms, machine guns, bazookas, and demolition or explosives. They had a bunch of us out there training and going through those schools and they decided that they needed replacements sent back overseas.

(*Note: this is probably an expression of contempt for all the stateside rules, regulations, and drills imposed on Marines who had just spent months fighting for their lives.)

OKINAWA and CHINA

By the time we got to Guam the announcement was made that the war was over in Germany so we had to go on into Okinawa. Okinawa was a big island, heavily populated, and they were still fighting over there. The Japanese had about two-thirds of Okinawa taken. They had done some hard fighting over there.

There were two of us that drove down a roadway on the lower end of the lines one morning in a jeep. We saw one (a Japanese soldier) get up out of a cane field. We stopped and we're going to get him, take him prisoner. He jumped up with some kind of pistol and started shooting at us. We plugged him, left him. We went on down to the lower end, to the cliffs and we could see where they had dropped off the cliffs.

(Note: the Japanese told the native Okinawans that the American soldiers would rape and torture them. Untold numbers of civilians committed suicide by jumping off the cliffs into the sea rather than risk barbarism at the hands of the Americans.)

On the way back we spotted a boy and girl walking along the little road. I guess they had sense enough to know not to make any fight out of it. We rolled up and took those two as prisoners. We carried them back to camp with us and turned them over to the battalion commander.

We were up on a ridge right next to the ocean, next to a big cane field, about 30 or 40 acres. We heard an explosion and looked down in the cane field and there was a Nip (short for Nippon, a Japanese soldier) flip-flopping up in the air. He had blown himself up with a hand grenade.

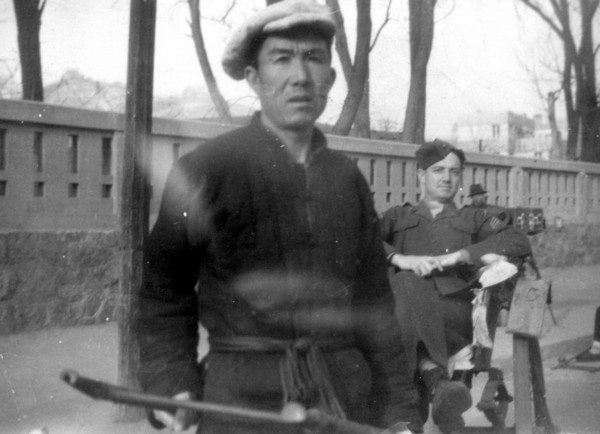

Soldiers on both sides just wanted to get back home, no doubt including the deceased owner of this photograph.

We were sitting there one night on that same hill, we had to keep so many on guard. There was a little road that ran up and down from the ocean. A couple of us were just sitting there, talking, shooting the breeze. It was a moonlit night and all of a sudden we discovered: here's a Nip coming up the trail, walking our way. We were sitting right in the trail nearly. I jumped over and grabbed my M1 rifle. I shot at that fool until I emptied my rifle and, durn, if he didn't run off. The next morning I discovered I was shooting into the ground.

Some of them (Marines) would capture two or three of them (Japanese) and then act like they weren’t watching them. We were already mad at them for all the tricks they had been pulling on us. They would act like they weren't watching them and (the Japanese prisoners) would break and run. (The Marines) would just shoot them down.

I saw some of them (fellow Marines) crack. It's pretty pitiful to see some of them cracked up, nerves shot, crying. One old boy I remember. There were a bunch of caves on Okinawa, and I think he was from Brooklyn. He wanted to prove to everybody that he was a mean dog and he went into these caves where there were Nips. He finally cracked up. He wasn't as brave as he thought he was.

We finished at Okinawa and moved back to Guam again, getting ready for (the invasion of) Japan. I volunteered and went into a suicide platoon because, by that time, they had me believing I was really a Marine. We were just lucky that (President) Truman dropped the (atomic) bomb and we didn't have to go into combat because that would've been a sure enough dangerous outfit to have been in.

When they dropped the bomb on Hiroshima they had a big celebration that night. They drug out all the beer and the booze. We thought that was the end of it. We didn't know that they would have to drop another bomb.

After that, there were some Japanese in China. They had all surrendered and we had to go after them and get them, look after them, and keep them together. By that time I had spent all my money and I decided China would be a good place to go. There wasn't any other place I could go and save my money so I went to Sing Tao, China. It was cold there. This was about 1944. After that we loaded up and I got to come back home.

Harvey McCollum using public transportation in China.

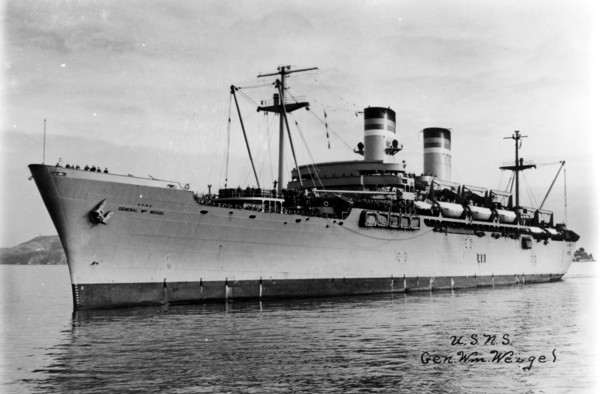

The troop transport ship that brought Harvey McCollum home for good.

By the time I spent that much time in the Marines, there was a lot of difference in the way I looked at the country.

**********

My father never brought up the war unless he was asked about it, and even then, he would gloss over anything horrific and focus on some prank, funny mistake, or trivia unrelated to battle. For example, he mentioned actor Gary Cooper, on a USO tour in New Guinea, sitting down with him and some other Marines, eating the same chow and being "one of the boys."

According to my mother, for years after they were married in 1947, my father had nightmares about the war. His Silver Star medal and citation sat for decades in a shoe box containing other wartime souvenirs until my mother had both framed. My father never acknowledged their presence on the den wall.

However, there was one aspect of his wartime service that couldn't be ignored: his two tattoos, especially the one on his left forearm with the words Death Before Dishonor and, below that, the name of his Australian girlfriend.

Hazel and Harvey McCollum, circa 1969, at the house they built on Harlow Hill outside Summerville. The other tattoo is near my father's right shoulder.

To compound the issue, when the last of his nine siblings was born during the war, my youngest aunt was named after both my father's and his brother's (Bill, also a Marine serving in the Pacific) Australian girlfriends. Fortunately for my mother, my Aunt Sue goes by the more conventional name, not the one tattooed on my father's arm.

This was a source of endless teasing of both parents on my part, and a way of extracting at least a few details about my father's war record.

**********

My father grew up dirt poor, and by all accounts was the victim of physical abuse by his father when he was a child working on the farm. Add to that the years spent as a Marine fighting under the most dangerous conditions imaginable, and you'd think he would have become a violent basket case. For whatever reason, he was just the opposite. I can only remember one spanking I received as a kid, and that was a mild rebuke. I knew better than to misbehave (or at least, get caught) because the last thing you wanted from my father was "the look" that meant you had screwed up royally.

My father was a quiet man who plotted his own course in life, never followed the crowd, and never, ever, looked back. He had a gentle manner, a dry wit, and a stubborn streak if pushed. I suspect his biggest motivation in life after returning home from the war was to control his own destiny, and if that meant quitting his mill job and striking out on his own, often working 16-hour days and almost going broke in the early years (Thanks, Kayo!), so be it.

He was a good father, husband, and Methodist. Despite not always following his example, I was lucky to have it. To this day, whenever I have a tough decision to make, invariably I ask myself, "What would Harvey do?"

**********

In 2000, my brother-in-law, Gerald Pickle, saw a book about World War II in a bookstore.

He opened the index, saw my father's name, flipped to page 267, and found the following:

"A brother's gift saved the life of Sgt. William C. McCollum of Cedar Bluff, Alabama. The sibling, Sgt. Warren Harvey McCollum, attached to an artillery outfit, had presented infantryman Bill with a pistol just before the Gloucester campaign. While creeping forward in the gloom with his unit, Bill found himself face-to-face with a rifle-armed Jap.

Bill swung out his tommy gun and fired, but heard only a click. That's when he realized that the magazine of his weapon had dropped out! The Jap, perhaps more surprised than Bill at the sudden meeting, failed to fire, giving Bill time to draw the gift from his shoulder holster and abruptly end the tete-a-tete with a single shot."